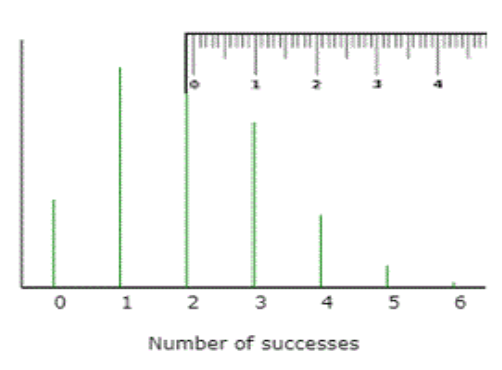

This would increase the probability of a correct guess to 0.25, and so the probability model would need to change as well. If there are only 4 cards, the probability of a correct guess increases to 0.25. So, with 25 attempts, the expected value would be

\(25(0.25) = 6.25\) with an SD of

\(\sqrt{25(0.25)(0.75)} = 2.17\text{.}\) So

\(6.25 + 2(2.17) = 10.59 \approx 11\text{.}\) Notice that this “cutoff” value went up (10 or 11 vs. 9). This is because guessing is more likely to do well so we need more evidence that someone is not guessing. Also, using the applet,

\(P(C \geq 10) = 0.097\) and

\(P(C \geq 11) = 0.044\text{.}\)