Does this result provide strong evidence that these students do better than guessing in discriminating among the colas? Address this question with an appropriate test of significance, including a statement of the hypotheses and a p-value calculation or estimation. Be sure to clarify which procedure you used to determine the p-value and why. Summarize your conclusion, and explain the reasoning process by which it follows.

Solution.

We can define \(\pi\) to be the probability that these students correctly identify the odd soda. (In other words, if this group of students were to repeat this process under identical conditions indefinitely, \(\pi\) represents the long-term fraction that they would identify correctly.) The null hypothesis asserts that the students are just guessing, which means that their success probability is one-third (\(H_0: \pi = 1/3\)). The alternative hypothesis is that students do better than guessing, which means that their success probability is greater than one-third (\(H_a: \pi > 1/3\)).

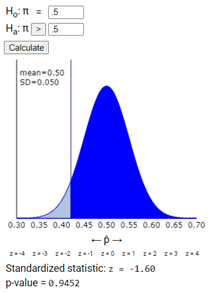

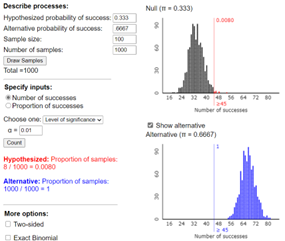

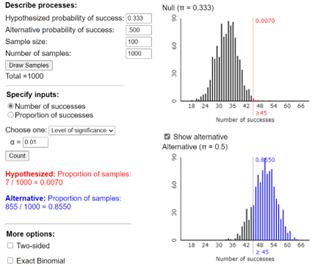

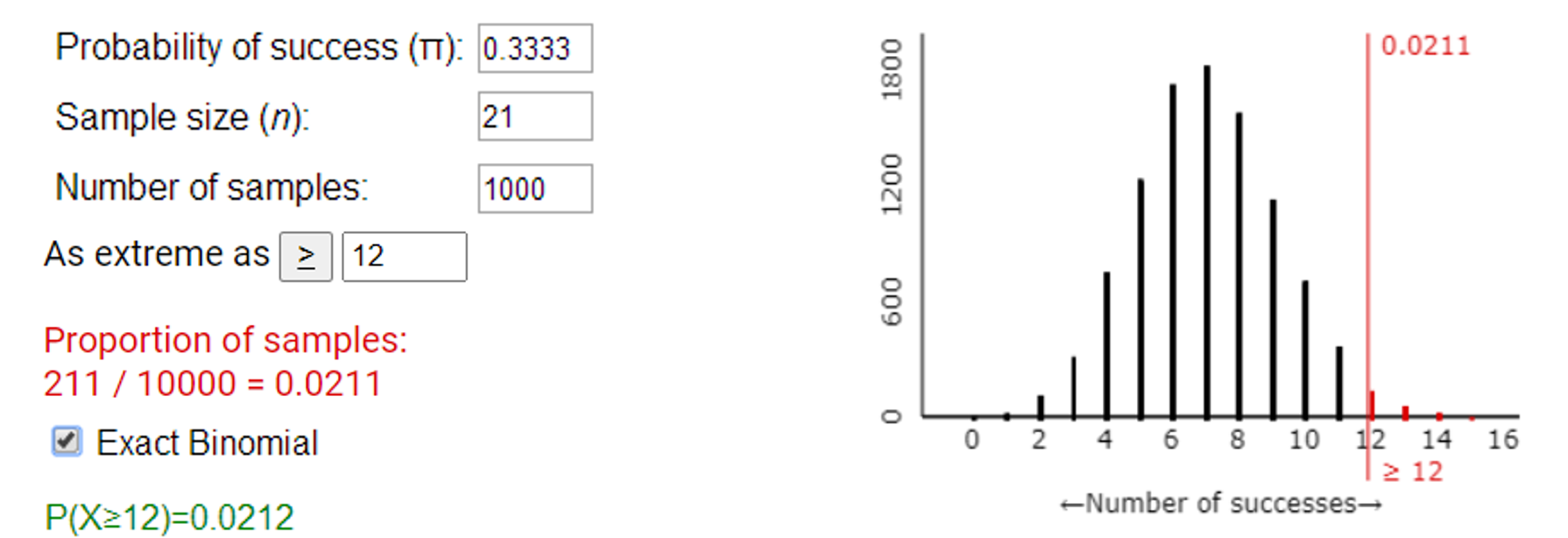

Under the null hypothesis that the students are just guessing among the three cups, \(X\) (the number of correct identifications) has a binomial distribution with parameters \(n = 21\) and \(\pi = 1/3\text{.}\) The normal distribution would probably not be valid here as we do not satisfy the conditions: \(n \times \pi = 21(1/3) = 7 < 10\text{.}\) We could simulate observations from this Binomial process using the One Proportion Inference applet, and see how often we observe 12 or more correct identifications just by chance:

R Output.

Or we could calculate the exact Binomial probability using R:

iscambinomprob(k=12, n=21, prob=.3333, lower.tail=FALSE)

# Probability 12 and above = 0.02117713

iscambinomtest(observed=12, n=21, hyp=.3333, alternative="greater")

# p-value: 0.021177

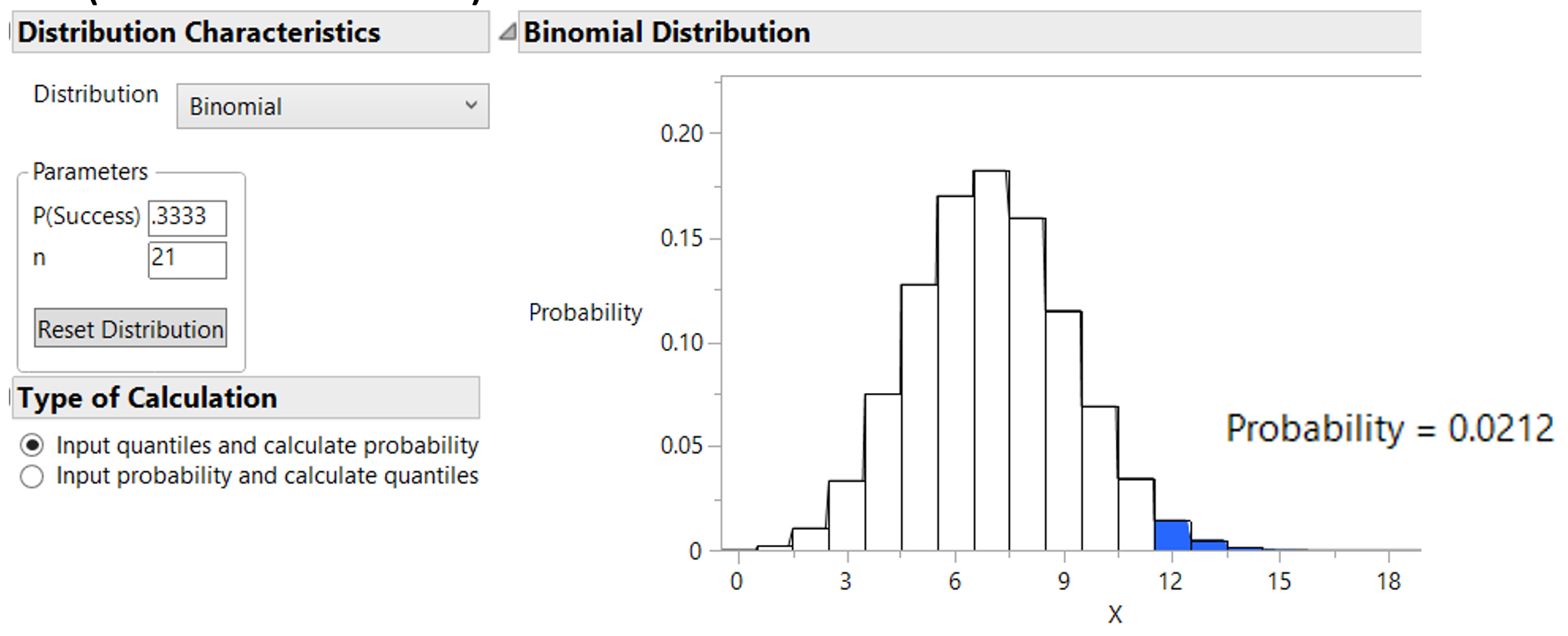

JMP Output.

Or we could calculate the exact Binomial probability using JMP:

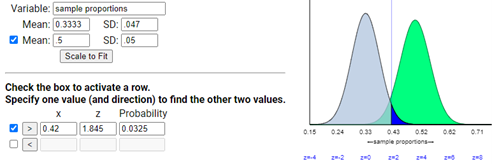

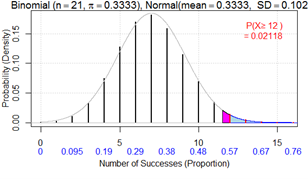

Notice the normal approximation (using R) does not provide a great estimate of this p-value:

iscamonepropztest(observed=12, n=21, hyp=.3333, alternative="greater")

# z-statistic: 2.31, p-value: 0.01031

But the normal approximation does improve with the continuity correction:

iscambinomnorm(k=12, n=21, prob=.3333, direction="above")

# binomial: 0.02118

# normal approx: 0.01031

# normal approx with continuity: 0.01860

This p-value reveals that if the students were just guessing, there’s only about a 2% probability of "by chance" getting 12 or more correct identifications among 21 trials. In other words, if we repeated this study over and over, and if students were just guessing each time, then a result at least this favorable would occur in only about 2% of the studies. Because this probability is quite small, we have fairly strong evidence that these students’ process in fact is better than guessing in discriminating among the colas (i.e., that \(\pi > 1/3\)). Because the sodas were randomly placed in the cups and (presumably) the teacher kept other variables (e.g., temperature, age) constant, this study attempted to isolate the taste and appearance of the sodas as the sole reasons for their selection.