We want to find

\(P(\bar{x}_{1}-\bar{x}_{2} \gt 3) + P(\bar{x}_{1}-\bar{x}_{2} \lt -3)\text{.}\)

Let us first determine whether the independence condition is satisfied and whether normal approximation will be appropriate. We have two random samples, and the samples are distinct and independent of each other. The sample sizes are each less than 10% of total population of runners. Also, because the sample sizes n1 and n2 are both 50, and

\(50 \ge 30\text{,}\) we don’t need the distribution of all run times to be nearly normal. With these conditions met, we have shown that the distribution of

\(\bar{x}_{1}-\bar{x}_{2}\) is nearly normal.

\begin{gather*}

\mu_{\bar{x}_{1}-\bar{x}_{2}} = \mu_{1}-\mu_{2} = 94.52 - 94.52 = 0\\

\sigma_{\bar{x}_{1}-\bar{x}_{2}} = \sqrt{\frac{\sigma_{1}^2}{n_{1}}+\frac{\sigma_{2}^2}{n_{2}}} = \sqrt{\frac{8.97^2}{50}+\frac{8.97^2}{50}} =1.79

\end{gather*}

To find \(P(\bar{x}_{1}-\bar{x}_{2} \gt 3)\text{,}\) we use the calculated mean and standard deviation of \(\bar{x}_{1}-\bar{x}_{2}\) to first find a Z-score for the difference of interest, which is 3.

\begin{gather*}

Z=\frac{x-\mu}{\sigma} = \frac{3-0}{1.79} = 1.676

\end{gather*}

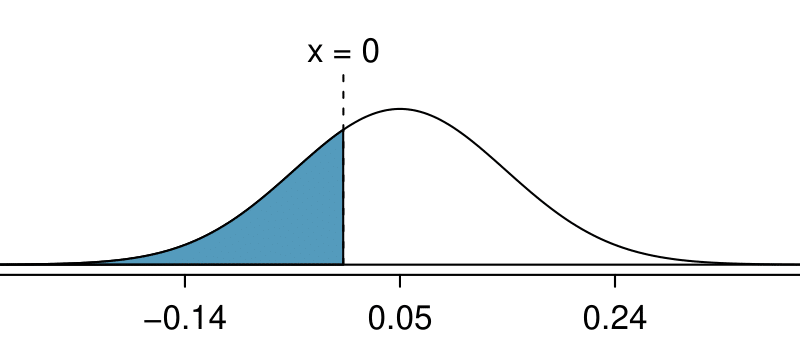

Using technology, to find the area to the right of 1.676 under the standard normal curve, we have:

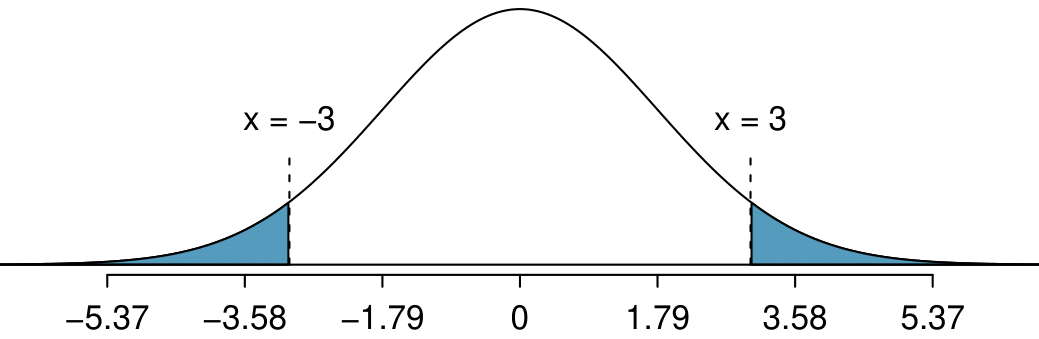

\(P(\bar{x}_{1}-\bar{x}_{2} \gt 3) \approx P(Z \gt 1.676) = 0.047\text{.}\) Because the normal distribution of interest is centered at zero, the

\(P(\bar{x}_{1}-\bar{x}_{2} \lt -33)\) tail area will have the same size. So to get the total of the two tail areas, we double 0.047. Even though the samples are from the same population of runners, there is still a

\(2 \times 0.047 = 0.094\) probability, or a 9.4% chance, that the sample means will differ by more than 3 minutes.