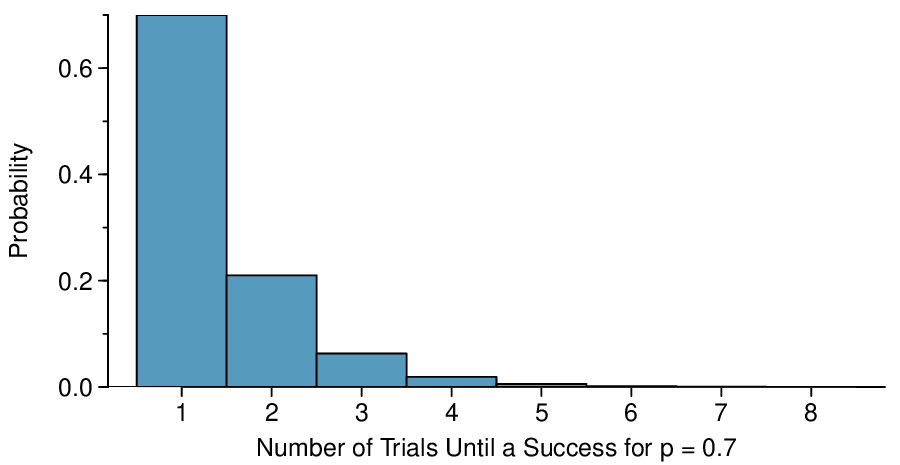

The probability of stopping after the first person is just the chance the first person will not exceed her (or his) deductible: 0.7. The probability the second person is the first to exceed her deductible is

\begin{align*}

\amp P(\text{ second person is the first to exceed deductible } )\\

\amp = P(\text{ the first won't, the second will } ) = (0.7)(0.3) = 0.21

\end{align*}

Likewise, the probability it will be the third case is

\((0.3)(0.3)(0.7) = 0.063\text{.}\)

If the first success is on the

\(x^{th}\) person, then there are

\(x-1\) failures and finally 1 success, which corresponds to the probability

\((0.7)^{x-1}(0.7)\text{.}\) This is the same as

\((1-0.7)^{x-1}(0.7)\text{.}\)