Section 4.1 Follow the Data

An old adage in detective work is to, "follow the money." In data science, one key to success is to "follow the data." In most cases, a data scientist will not help to design an information system from scratch. Instead, there will be several or many legacy systems where data resides; a big part of the challenge to the data scientist lies in integrating those systems.

Hate to nag, but have you had a checkup lately? If you have been to the doctor for any reason you may recall that the doctor’s office is awash with data. First off, the doctor has loads of digital sensors, everything from blood pressure monitors to ultrasound machines, and all of these produce mountains of data. Perhaps of greater concern in this era is the debate about health insurance, making the doctor’s office one of the big jumping off points for financial and insurance data. One of the notable "features" of the U.S. healthcare system is our most common method of healthcare delivery: paying by the procedure. When you experience a "procedure" at the doctor’s office, whether it is a consultation, an examination, a test, or something else, this initiates a chain of data events with far reaching consequences.

If your doctor is typical, the starting point of these events is a paper form. Have you ever looked at one of these in detail? Most of the form will be covered by a large matrix of procedures and codes. Although some of the better equipped places may use this form digitally on a tablet or other computer, paper forms are still ubiquitous. Somewhere either in the doctor’s office or at an outsourced service company, the data on the paper form are entered into a system that begins the insurance reimbursement and/or billing process.

Where do these procedure data go? What other kinds of data (such as patient account information) may get attached to them in a subsequent step? What kinds of networks do these linked data travel over, and what kind of security do they have? How many steps are there in processing the data before they get to the insurance company? How does the insurance company process and analyze the data before issuing the reimbursement? How is the money "transmitted" once the insurance company’s systems have given approval to the reimbursement? These questions barely scratch the surface: there are dozens or hundreds of processing steps that we haven’t yet imagined.

It is easy to see from this example, that the likelihood of being able to throw it all out and start designing a better or at least more standardized system from scratch is nil. But what if you had the job of improving the efficiency of the system, or auditing the insurance reimbursements to make sure they were compliant with insurance records, or using the data to detect and predict outbreaks and epidemics, or providing feedback to consumers about how much they can expect to pay out of pocket for various procedures?

The critical starting point for your project would be to follow the data. You would need to be like a detective, finding out in a substantial degree of detail the content, format, senders, receivers, transmission methods, repositories, and users of data at each step in the process and at each organization where the data are processed or housed.

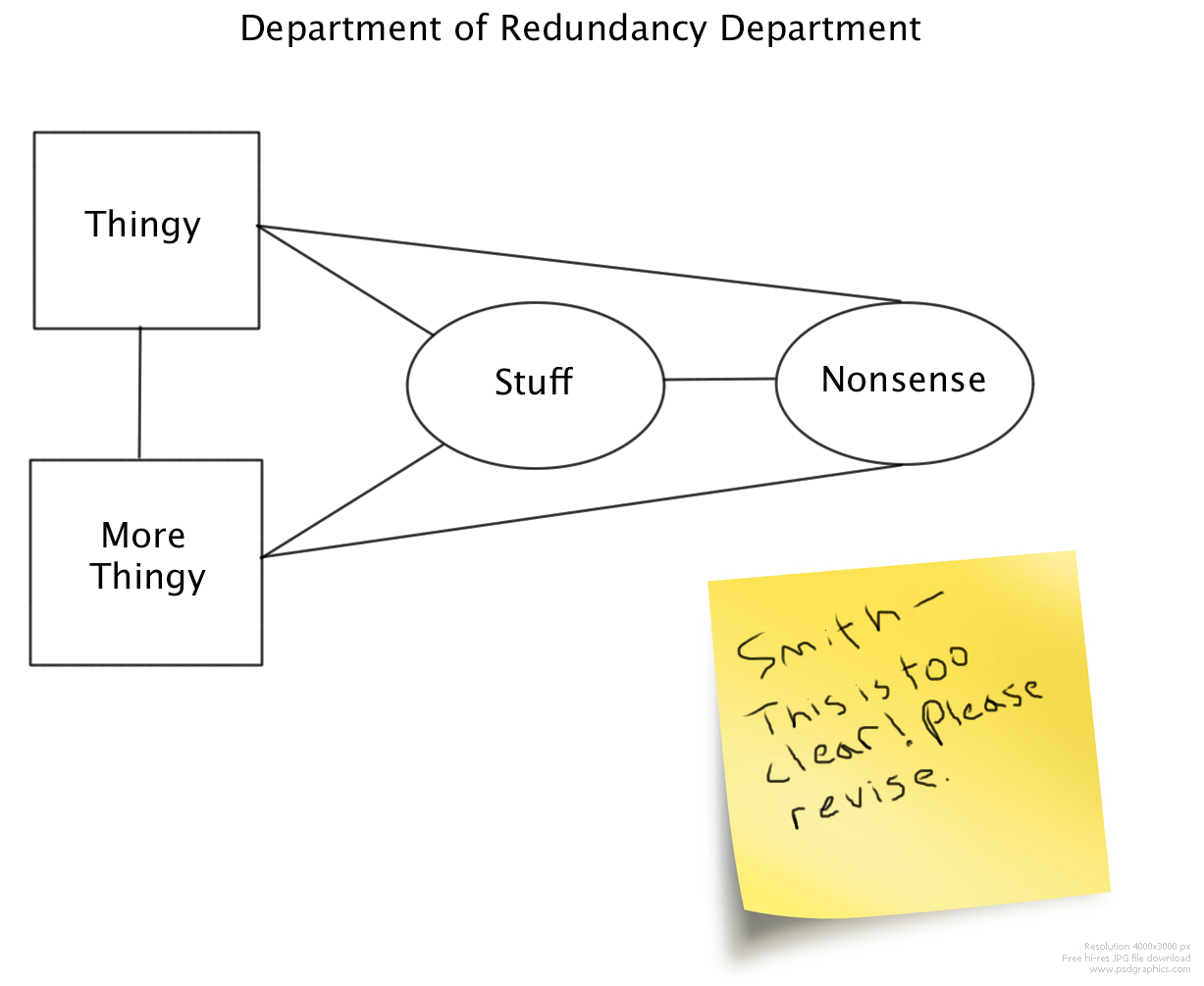

Fortunately there is an extensive area of study and practice called "data modeling" that provides theories, strategies, and tools to help with the data scientist’s goal of following the data. These ideas started in earnest in the 1970s with the introduction by computer scientist Ed Yourdon of a methodology called Data Flow Diagrams. A more contemporary approach, that is strongly linked with the practice of creating relational databases, is called the entity relationship model. Professionals using this model develop Entity Relationship Diagrams (ERDs) that describe the structure and movement of data in a system.

Entity-relationship modeling occurs at different levels ranging from an abstract conceptual level to a physical storage level. At the conceptual level an entity is an object or thing, usually something in the real world. In the doctor’s office example, one important "object" is the patient. Another entity is the doctor. The patient and the doctor are linked by a relationship: in modern health care lingo this is the "provider" relationship. If the patient is Mr. X and the doctor is Dr. Y, the provider relationship provides a bidirectional link:

Naturally there is a range of data that can represent Mr. X: name address, age, etc. Likewise, there is data that represents Dr. Y’s years of experience as a doctor, specialty areas, certifications, licenses. Importantly, there is also a chunk of data that represents the linkage between X and Y, and this is the relationship.

Creating an ERD requires investigating and enumerating all of the entities, such as patients and doctors, as well as all of the relationships that may exist among them. As the beginning of the chapter suggested, this may have to occur across multiple organizations (e.g., the doctor’s office and the insurance company) depending upon the purpose of the information system that is being designed. Eventually, the ERDs must become detailed enough that they can serve as a specification for the physical storage in a database.

In an application area like health care, there are so many choices for different ways of designing the data that it requires some experience and possibly some "art" to create a workable system. Part of the art lies in understanding the users’ current information needs and anticipating how those needs may change in the future. If an organization is redesigning a system, adding to a system, or creating brand new systems, they are doing so in the expectation of a future benefit. This benefit may arise from greater efficiency, reduction of errors/inaccuracies, or the hope of providing a new product or service with the enhanced information capabilities.

Whatever the goal, the data scientist has an important and difficult challenge of taking the methods of today including paper forms and manual data entry to imagine the methods of tomorrow. Follow the data!

In the next chapter we look at one of the most common and most useful ways of organizing data, namely in a rectangular structure that has rows and columns. This rectangular arrangement of data appears in spreadsheets and databases that are used for a variety of applications. Understanding how these rows and columns are organized is critical to most tasks in data science.

You have attempted of activities on this page.