Section 3.21 Implementing an Unordered List: Arrays

In order to implement an unordered list, we will first do so by using an array. In Kotlin, an array is very similar to a list. Just like a list, an array is a collection of items, where each item has an index, starting from zero. The difference is that arrays are much more limited in functionality than lists. When creating an array, you need to specify its size, and then you are unable to modify its size once it has been created. You also need to specify initial values for all items in the array. Once the array has been created, you can change the value at a particular index location, but there’s no built-in capability for inserting a new item between others, or at the end. Likewise, there’s no built-in capability for removing an item. The only two supported operations for an array, once it has been created, are indexing and assignment to an array index.

It sounds as though an array is just a limited version of a list. So why would we bother with it? It’s not that arrays are better than lists. Rather, arrays are the underlying mechanism on which lists are built in Kotlin. If we were to look at the actual programming code for the Kotlin language itself that implements default lists, we would see that they use arrays.

Therefore, even though Kotlin provides us with capable lists that do all of the detailed work with arrays underneath, we are going to implement some of that ourselves. It helps us learn about how lists are actually implemented in a programming language, and it also helps us continue to learn about ADTs and data structures. In the following section, we will implement a list using an entirely different mechanism called a linked list, and so implementing a list with an array helps give us a basis for comparison.

Subsection 3.21.1 More details about arrays

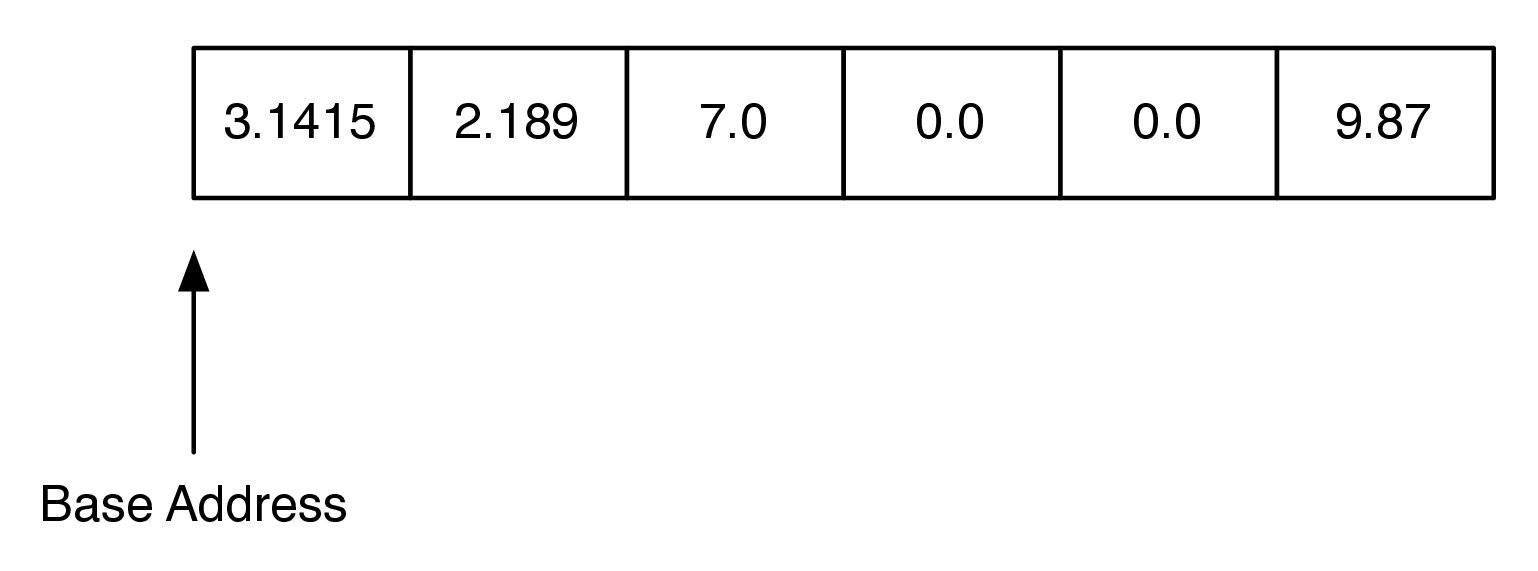

The best way to think about an array is that it is one continuous block of bytes in the computer’s memory. This block is divided up into \(n\)-byte chunks where \(n\) is based on the data type that is stored in the array. Figure 3.21.1 illustrates the an array that is sized to hold six floating point values represented as

Double.

double Point NumbersIn Kotlin, each floating point number uses 64 bytes of memory. So the array in Figure 3.21.1 would use a total of 384 bytes. The base address is the location in memory where the array starts. If you do code like the following:

fun main() {

val data = doubleArrayOf(3.1415, 2.189, 7.0, 0.0, 0.0, 9.87)

println(data)

}

We get this output showing the reference address after the

@:

$ [D@27bc2616

The address is very important because an array implements the index operator using a very simple calculation:

itemAddress = baseAddress + index * sizeOfObject

For example, suppose that our array starts at location

0x000030, which is 48 in decimal. To calculate the location of the object at position 4 in the array we do the arithmetic: \(48 + 4 \cdot 64 = 304\text{.}\) This kind of calculation is \(O(1)\text{.}\) Of course this comes with some risks. First, since the size of an array is fixed, one cannot just add things on to the end of the array indefinitely without some serious consequences. Second, in some languages, like C, the bounds of the array are not even checked, so even though your array has only six elements in it, assigning a value to index 7 will not result in a runtime error. As you might imagine this can cause big problems that are hard to track down. In the Linux operating system, accessing a value that is beyond the boundaries of an array will often produce the rather uninformative error message “segmentation violation.”

In Kotlin, we have been using both the

List and MutableList classes, which use an array underneath. The strategy that Kotlin uses is as follows:

-

Kotlin uses an array that holds references (called pointers in C) to other objects.

-

Kotlin uses a strategy called over-allocation to allocate an array with space for more objects than is needed initially.

-

When the initial array is finally filled up, a new, bigger array is over-allocated and the contents of the old array are copied to the new array.

The implications of this strategy are pretty amazing. Let’s look at what they are first before we dive into the implementation or prove anything.

-

Accessing an item at a specific location is \(O(1)\text{.}\)

-

Removing from the end of the list is \(O(1)\text{.}\)

-

Removing from elsewhere in the list is \(O(n)\) in the worst case.

-

Inserting an item into an arbitrary position is \(O(n)\) in the worst case.

Subsection 3.21.2 Building our own list: setting up the array in Kotlin

Let’s start using the above ideas to create our own implementation of an unordered list, using an array to store the data. We’ll use a private variable within our class named

array, which will store the contents for our unsorted list. As explained above, we need to provide an initial size for that array, as well as initial values, with more space than we need. We’ll start with an array of size 16 to get things started, and create new bigger arrays in the future as we need them. We’ll also create a variable to keep track of how much of the array we are currently using.

The following code below isn’t quite correct, but shows the idea of what we’re trying to do. We’ll then fix it.

class ArrayUnorderedList<T> : UnorderedListADT<T> {

private var array = arrayOfNulls<T?>(16) // initialize to size 16

private var usedCount = 0 // how many places we currently use

...

}

Kotlin has a built-in function named

arrayOfNulls, which we use above to create an array of size 16. We use T? as the type instead of just T to indicate the type, because we are using null values for spaces that are not being used. The above code is right in principle, but Kotlin will not permit us create an array of a generic types (i.e., where the type is a parameter, like <T> in this code). Therefore, we have to use a trick: we instead will make it an array of type Any?. Any? is a class in Kotlin for which all other classes are subclasses. The ? indicates that null values are permitted. Therefore, with this change, our code (which is still not quite right yet) looks like:

Any?.class ArrayUnorderedList<T> : UnorderedListADT<T> {

private var array = arrayOfNulls<Any?>(16) // initialize to size 16

private var usedCount = 0 // how many places we currently use

...

}

The above approach is closer, but it results in the type of our variable

array being Array<Any?>. Kotlin will happily let us put items of type T into the array, but the problem occurs when we try to get an item out of our array. Here’s some sample code that shows the problem:

fun putInArrayThenReturn(T item): T? {

array[0] = item

return array[0]

}

This function takes

item as a parameter, places it in the index-0 location of the array, then returns it. Kotlin reports an error at the return statement, where it indicates a mismatch in return types: the function expects something of type T to be returned, but it is instead returning something of type Any?. The simplest fix is to tell Kotlin when we create the array that we intend to think of it as an array of type T?, even though we have applied a trick of making it a type of Any?. To that end, here’s our next (almost there!) update to creating our array:

class ArrayUnorderedList<T> : UnorderedListADT<T> {

private var array = arrayOfNulls<Any?>(16) as Array<T?>

private var usedCount = 0

...

}

The above approach actually works, though we get a warning. The warning is concerning the code we added at the end of the line creating the array, where we added the code

as Array<T?>. This is called a cast, and it indicates that we are telling Kotlin to treat an array of Any? as an array of type T?. If we write our code correctly and only put items of type T? in the array, this will all work. However, if we put something in that array that is not of type T?, Kotlin will happily do it, because the array is really of type Any?. This would cause an exception when the program runs when we try to get that item back out and assign it to a variable of type T?. This approach is essential, however, so we will tell Kotlin to suppress that warning. Typically, warnings shouldn’t be suppressed, and this should be considered to be poor style in general. But in this particular case this is considered to be standard procedure to work around the fact that Kotlin has this particular limitation for arrays. With all of that said, here is the correct working start to our class:

class ArrayUnorderedList<T> : UnorderedListADT<T> {

@Suppress("UNCHECKED_CAST")

private var array = arrayOfNulls<Any?>(16) as Array<T?>

private var usedCount = 0

...

}

Subsection 3.21.3 Implementing more of the unordered list

Now that we have the array set up, we can now implement some of the member functions that we need. The code below shows code

add, addLast functions, as well as for get.

add, addLast, and getclass ArrayUnorderedList<T> : UnorderedListADT<T> {

// Create an initial array, of size 1

@Suppress("UNCHECKED_CAST")

private var array = arrayOfNulls<Any?>(10) as Array<T?>

// Keeps track of the number of locations in the

// array that have been used

private var usedCount = 0

// Add a new item at the specified index.

override fun add(index: Int, item: T) {

// Make sure that index is for an allowed location

if (index !in 0..usedCount) {

throw Exception("Index out of range")

}

// If entire array is used, double its capacity

if (usedCount == array.count()) {

array = array.copyOf(array.count() * 2)

}

// Move values out of the way

for (i in usedCount downTo index + 1) {

array[i] = array[i - 1]

}

array[index] = item

usedCount++

}

// Add a new item to the end of the list.

override fun addLast(item: T) {

add(usedCount, item)

}

// Set the value of an item at the specified index.

override fun set(index: Int, item: T) {

if (index in 0..< usedCount) {

array[index] = item

} else {

throw Exception("Index out of range")

}

}

// Return item at specified index.

override fun get(index: Int): T {

if (index in 0..<usedCount) {

return requireNotNull(array[index])

} else {

throw Exception("Index out of range")

}

}

}

Let’s look first at the

add function, beginning on line 12. The first thing add does is, in lines 14-16, is make sure that the index at which are an adding an item is appropriate. The variable usedCount indicate how much of the array we are using. In other words, it indicates how many values we have stored in the array. If index is equal to usedCount, this indicates that we are appending a new value at the end of the array. If it is less than that, then we are are putting the new value in a location that previously had a value, and we shift all of the other values over to make room.

The next check we do is to see if there is room in the array to store a new value. In line 19, we check to see if the number of spaces in the array that we are using is equal to the size of the array itself. If that is the case, line 20 reassigns our array to a new one, which is a copy of the original one but with double its capacity. The old array, which no longer is referred to by any variables, is garbage collected.

There are many methods that could be used for resizing the array. Some implementations double the size of the array every time as we do here, some use a multiplier of 1.5, and some use powers of two. Doubling the array size leads to a bit more wasted space at any one time, but is much easier to analyze.

Once we are confident we have enough room in the array for the new value, we make room at the necessary location for the new value in lines 24-26. The key to doing this correctly is to realize that as you are shifting values in the array you do not want to overwrite any important data. The way to do this is to work from the end of the list back toward the insertion point, copying data forward. Our implementation does this in lines 24-26. Note how the loop index goes downward to ensure that we are copying existing data into the unused part of the array first, and then subsequent values are copied over old values that have already been shifted. If the loop had started at the insertion point and copied that value to the next larger index position in the array, the old value would have been lost forever.

Finally, in lines 27-28, we put the new item in the array, and increment

usedCount. Note that if index, which is the location of the new value, is the same as usedCount, that means that nothing needs to be shifted over. The loop in lines 24-26 will occur zero times in that scenario.

The second member function

addLast, which doesn’t take an index value, is a convenience function for inserting the new item at the end. It is simply a one-line function which calls the other add function, indicating the location to be at the very end of the current used values, which is indicated by the value usedCount.

Let’s look at the big O performance for add. To do this, let’s think of add as two separate operations: one operation expands the array if necessary, and the other slides values down to make room for the new value. The performance of sliding values down to make room is \(O(n)\text{,}\) since in the worst case we want to insert something at index 0, and we have to shift the entire array forward by one. On average we will only need to shift half of the array, but this is still \(O(n)\text{.}\)

Regarding the expansion operation, how much work does that take every time we insert something? Most of the time, it takes no work at all apart from checking to see if there is room in the array, which is \(O(1)\text{.}\) Occasionally, the array does need to be expanded, but remarkably, the amount of work that needs to be done averages out to \(O(1)\) as well. Let’s see why. The only time that the expansion operation takes more than \(O(1)\) work is when

usedCount is a power of 2. When usedCount is a power of 2 then the cost to expand the array is \(O(usedCount)\text{.}\) We can therefore summarize the cost to expand the array for adding the \(i_{th}\) item as follows:

\begin{equation*}

c_i =

\begin{cases}

O(usedCount) \text{ if } i \text{ is a power of 2} \\

O(1) \text{ otherwise}

\end{cases}

\end{equation*}

Since the expensive cost of copying

usedCount items occurs relatively infrequently, we spread the cost out, or amortize, the cost of insertion over all of the adds. When we do this the cost of any one add averages out to \(O(1)\text{.}\) For example, consider the case where you have already added 16 items. Each of the previous 16 adds cost you just one operation to check that array is large enough to hold 16 items. When the 17th item is added, a new array of size 32 is allocated and the 16 old items are copied. But now you have room in the array for 16 additional low cost appends. Mathematically we can show this as follows:

\begin{equation*}

\begin{aligned}

cost_{total} &= n + \sum_{j=0}^{\log_2{n}}{2^j} \\

&= n + 2n \\

&= 3n \\

\end{aligned}

\end{equation*}

The summation in the previous equation may not be obvious to you, so let’s think about that a bit more. The sum goes from zero to \(\log_2{n}\text{.}\) The upper bound on the summation tells us how many times we need to double the size of the array. The term \(2^j\) accounts for the copies that we need to do when the array is doubled. Since the total cost to append n items is \(3n\text{,}\) the cost for a single item is \(3n/n = 3\text{.}\) Because the cost is a constant we say that it is \(O(1)\text{.}\) This kind of analysis is called amortized analysis and is very useful in analyzing more advanced algorithms.

Let us now turn to the

set and get functions, which are also in Listing 3.21.7, shown above. Recall as we discussed that the calculation required to find the memory location of the \(i_{th}\) item in an array is an \(O(1)\) arithmetic expression, so both of these operations are \(O(1)\text{.}\)

There are several other operations that we have not yet implemented for our list:

addFirst, indexOf, isEmpty, remove, removeAt, and size. We leave these enhancements as an exercise for you.

Here is a program that we used to test our class.

You have attempted of activities on this page.