By solving the second equation for

\(x\) and writing

\(x = y + 1\text{,}\) we find that

\(y+1 = y^2 - 1\text{.}\) Hence the curves intersect where

\(y^2 - y - 2 = 0\text{.}\) Thus, we find

\(y = -1\) or

\(y = 2\text{,}\) so the intersection points of the two curves are

\((0,-1)\) and

\((3,2)\text{.}\)

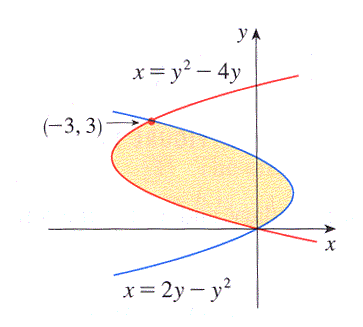

If we attempt to use vertical rectangles to slice up the area (as in the center graph of

Figure 6.1.5), we see that from

\(x = -1\) to

\(x = 0\) the curves that bound the top and bottom of the rectangle are one and the same. This suggests, as shown in the rightmost graph in the figure, that we try using horizontal rectangles.

Note that the width of a horizontal rectangle depends on

\(y\text{.}\) Between

\(y = -1\) and

\(y = 2\text{,}\) the right end of a representative rectangle is determined by the line

\(x = y+1\text{,}\) and the left end is determined by the parabola,

\(x = y^2-1\text{.}\) The thickness of the rectangle is

\(\Delta y\text{.}\)

Therefore, the area of the rectangle is

\begin{equation*}

A_{\text{rect} } = [(y+1) - (y^2-1)] \Delta y\text{,}

\end{equation*}

and the area between the two curves on the \(y\)-interval \([-1,2]\) is approximated by the Riemann sum

\begin{equation*}

A \approx \sum_{i=1}^{n} [(y_i+1)-(y_i^2-1)] \Delta y\text{.}

\end{equation*}

Taking the limit of the Riemann sum, it follows that the area of the region is

\begin{equation}

A = \int_{y=-1}^{y=2} [(y+1) - (y^2-1)] \, dy\text{.}\tag{6.1.3}

\end{equation}

We emphasize that we are integrating with respect to

\(y\text{;}\) this is because we chose to use horizontal rectangles whose widths depend on

\(y\) and whose thickness is denoted

\(\Delta y\text{.}\) It is a straightforward exercise to evaluate the integral in

Equation (6.1.3) and find that

\(A = \frac{9}{2}\text{.}\)