Section 2.7 Variables

One of the most powerful features of a programming language is the ability to manipulate

variables. A variable is a name that refers to a value.

Assignment statements create new variables and also give them values to refer to.

message = "What's up, Doc?"

n = 17

pi = 3.14159

This example makes three assignments. The first assigns the string value

"What's up, Doc?" to a new variable named

message. The second assigns the integer

17 to

n, and the third assigns the floating-point number

3.14159 to a variable called

pi.

The

assignment token,

=, should not be confused with

equality (we will see later that equality uses the

== token). The assignment statement links a

name, on the left hand side of the operator, with a

value, on the right hand side. This is why you will get an error if you enter:

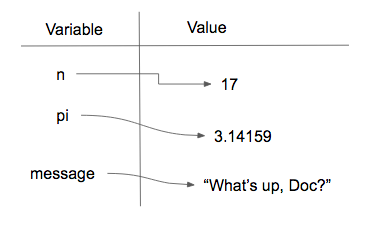

A common way to represent variables on paper is to write the name with an arrow pointing to the variable’s value. This kind of figure, known as a

reference diagram, is often called a

state snapshot because it shows what state each of the variables is in at a particular instant in time. (Think of it as the variable’s state of mind). This diagram shows the result of executing the assignment statements shown above.

If your program includes a variable in any expression, whenever that expression is executed it will produce the value that is linked to the variable at the time of execution. In other words, evaluating a variable looks up its value.

In each case the result is the value of the variable. To see this in even more detail, we can run the program using codelens.

Now, as you step through the statements, you can see the variables and the values they reference as those references are created.

We use variables in a program to “remember” things, like the current score at the football game. But variables are

variable. This means they can change over time, just like the scoreboard at a football game. You can assign a value to a variable, and later assign a different value to the same variable.

To see this, read and then run the following program. You’ll notice we change the value of

day three times, and on the third assignment we even give it a value that is of a different type.

A great deal of programming is about having the computer remember things. For example, we might want to keep track of the number of missed calls on your phone. Each time another call is missed, we will arrange to update or change the variable so that it will always reflect the correct value.

Any place in a Python program where a number or string is expected, you can put a variable name instead. The python interpreter will substitute the value for the variable name.

For example, we can find out the data type of the current value of a variable by putting the variable name inside the parentheses following the function name

type.

Checkpoint 2.7.4.

What is printed when the following statements execute?

day = "Thursday"

day = 32.5

day = 19

print(day)

Nothing is printed. A runtime error occurs.

It is legal to change the type of data that a variable holds in Python.

Thursday

This is the first value assigned to the variable day, but the next statements reassign that variable to new values.

32.5

This is the second value assigned to the variable day, but the next statement reassigns that variable to a new value.

19

The variable day will contain the last value assigned to it when it is printed.

You have attempted

of

activities on this page.