14.3. Complex numbers¶

As a running example for the rest of this chapter we will consider a class definition for complex numbers. Complex numbers are useful for many branches of mathematics and engineering, and many computations are performed using complex arithmetic. A complex number is the sum of a real part and an imaginary part, and is usually written in the form \(x + yi\), where \(x\) is the real part, \(y\) is the imaginary part, and \(i\) represents the square root of -1.

The following is a class definition for a user-defined type called

Complex:

class Complex

{

double real, imag;

public:

Complex () { }

Complex (double r, double i) { real = r; imag = i; }

};

Because this is a class definition, the instance variables real

and imag are private, and we have to include the label public:

to allow client code to invoke the constructors.

As usual, there are two constructors: one takes no parameters and does nothing; the other takes two parameters and uses them to initialize the instance variables.

So far there is no real advantage to making the instance variables private. Let’s make things a little more complicated; then the point might be clearer.

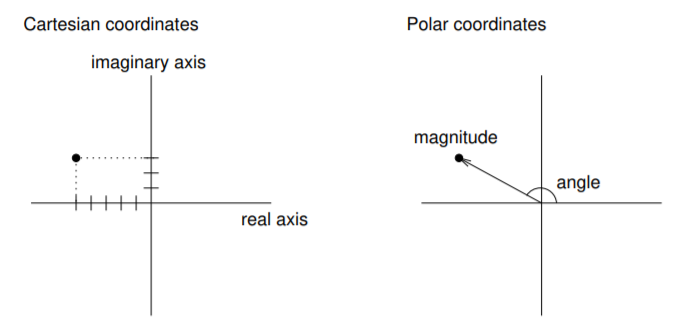

There is another common representation for complex numbers that is sometimes called “polar form” because it is based on polar coordinates. Instead of specifying the real part and the imaginary part of a point in the complex plane, polar coordinates specify the direction (or angle) of the point relative to the origin, and the distance (or magnitude) of the point.

The following figure shows the two coordinate systems graphically.

Complex numbers in polar coordinates are written \(r e^{i \theta}\), where \(r\) is the magnitude (radius), and \(\theta\) is the angle in radians.

Note

Fortunately, it is easy to convert from one form to another. To go from Cartesian to polar,

To go from polar to Cartesian,

So which representation should we use? Well, the whole reason there are multiple representations is that some operations are easier to perform in Cartesian coordinates (like addition), and others are easier in polar coordinates (like multiplication). One option is that we can write a class definition that uses both representations, and that converts between them automatically, as needed.

class Complex

{

double real, imag;

double mag, theta;

bool cartesian, polar;

public:

Complex () { cartesian = false; polar = false; }

Complex (double r, double i)

{

real = r; imag = i;

cartesian = true; polar = false;

}

};

There are now six instance variables, which means that this representation will take up more space than either of the others, but we will see that it is very versatile.

Four of the instance variables are self-explanatory. They contain the

real part, the imaginary part, the angle and the magnitude of the

complex number. The other two variables, cartesian and polar are

flags that indicate whether the corresponding values are currently

valid.

For example, the do-nothing constructor sets both flags to false to indicate that this object does not contain a valid complex number (yet), in either representation.

The second constructor uses the parameters to initialize the real and

imaginary parts, but it does not calculate the magnitude or angle.

Setting the polar flag to false warns other functions not to access

mag or theta until they have been set.

Now it should be clearer why we need to keep the instance variables private. If client programs were allowed unrestricted access, it would be easy for them to make errors by reading uninitialized values. In the next few sections, we will develop accessor functions that will make those kinds of mistakes impossible.

Take a look at the active code below, which demonstrates the separation of

interface and implementation using classes. In this code, we create a Triangle

object which is represented by three sides. In main, we print out the perimeter of

the triangle, which should be 12.

Now take a look at this second piece of active code. What if we decide we want

to represent a Triangle in a different way? Because the way we represent a

Triangle is private, we can easily change the implementation while keeping

the interface the same. Now, Triangle is represented by two sides and the

angle between them. Notice how our main function is the exact same as before.

Let’s write a constructor that uses parameters to initialize the magnitude and theta, but does not calculate the real and imaginary parts. Set the cartesian flag to false.

- True

- Correct! Client programs wouldn't have access to these values in the first place.

- False

- Incorrect! Keeping instance variables private prevents client programs from accessing them.

Q-4: Keeping instance variables private helps prevent client programs from making errors by reading uninitialized values.