18.8. 👩💻 Test Driven Development¶

At this point, you should be able to look at complete functions and tell what they do. Also, if you have been doing the exercises, you have written some small functions. As you write larger functions, you might start to have more difficulty, especially with runtime and semantic errors.

To deal with increasingly complex programs, we are going to suggest a technique called incremental development. The goal of incremental development is to avoid long debugging sessions by adding and testing only a small amount of code at a time.

- If you write unit tests before doing the incremental development, you will be able to track your progress as the code passes more and more of the tests. Alternatively, you can write additional tests at each stage of incremental development.

Then you will be able to check whether any code change you make at a later stage of development causes one of the earlier tests, which used to pass, to not pass any more.

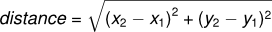

As an example, suppose you want to find the distance between two points, given by the coordinates (x1, y1) and (x2, y2). By the Pythagorean theorem, the distance is:

The first step is to consider what a distance function should look like in

Python. In other words, what are the inputs (parameters) and what is the output

(return value)?

In this case, the two points are the inputs, which we can represent using four parameters. The return value is the distance, which is a floating-point value.

Already we can write an outline of the function that captures our thinking so far.

def distance(x1, y1, x2, y2):

return None

Obviously, this version of the function doesn’t compute distances; it always returns None. But it is syntactically correct, and it will run, which means that we can test it before we make it more complicated.

The distance between any point and itself should be 0.

We call the distance function with sample inputs: (1,2, 1,2). The first 1,2 are the coordinates of the first point and the second 1,2 are the coordinates of the second point. What is the distance between these two points? Zero.

It’s not returning the correct answer, so we don’t pass the test. Let’s fix that.

Now we pass the test. But really, that’s not a sufficient test.

Extend the program …

On line 6, write another unit test (assert statement). Use (1,2, 4,6) as the parameters to the distance function. How far apart are these two points? Use that value (instead of 0) as the correct answer for this unit test.

On line 7, write another unit test. Use (0,0, 1,1) as the parameters to the distance function. How far apart are these two points? Use that value as the correct answer for this unit test.

Are there any other edge cases that you think you should consider? Perhaps points with negative numbers for x-values or y-values?

When testing a function, it is essential to know the right answer.

For the second test the horizontal distance equals 3 and the vertical distance equals 4; that way, the result is 5 (the hypotenuse of a 3-4-5 triangle). For the third test, we have a 1-1-sqrt(2) triangle.

The first test passes but the others fail since the distance function does not yet contain all the necessary steps.

At this point we have confirmed that the function is syntactically correct, and we can start adding lines of code. After each incremental change, we test the function again. If an error occurs at any point, we know where it must be — in the last line we added.

A logical first step in the computation is to find the differences x2- x1 and y2- y1.

We will store those values in temporary variables named dx and dy.

def distance(x1, y1, x2, y2):

dx = x2 - x1

dy = y2 - y1

return 0.0

Next we compute the sum of squares of dx and dy.

def distance(x1, y1, x2, y2):

dx = x2 - x1

dy = y2 - y1

dsquared = dx**2 + dy**2

return 0.0

Again, we could run the program at this stage and check the value of dsquared (which

should be 25).

Finally, using the fractional exponent 0.5 to find the square root,

we compute and return the result.

When you start out, you might add only a line or two of code at a time. As you gain more experience, you might find yourself writing and debugging bigger conceptual chunks. As you improve your programming skills you should find yourself managing bigger and bigger chunks: this is very similar to the way we learned to read letters, syllables, words, phrases, sentences, paragraphs, etc., or the way we learn to chunk music — from individual notes to chords, bars, phrases, and so on.

The key aspects of the process are:

Make sure you know what you are trying to accomplish. Then you can write appropriate unit tests.

Start with a working skeleton program and make small incremental changes. At any point, if there is an error, you will know exactly where it is.

Use temporary variables to hold intermediate values so that you can easily inspect and check them.

Once the program is working, you might want to consolidate multiple statements into compound expressions, but only do this if it does not make the program more difficult to read.